Evert Reflects on U.S. Open Memories and Broadcasting Career

Evert Reflects on U.S. Open Memories and Broadcasting Career

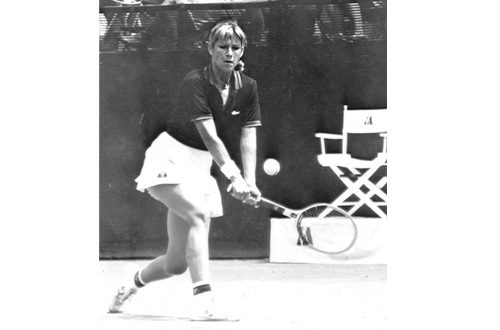

Every authentic tennis champion has a groundbreaking event in their evolution, a defining moment that propels them toward greatness, a critical turning point that permanently alters their life. For Chrissie Evert, that time was irrefutably in the golden summer of 1971, when she made a spectacular Grand Slam tournament debut at the U.S. Open on the lawns of Forest Hills, reaching the semifinals as a precocious 16-year-old who epitomized poise under pressure. The Floridian would compete in her nation’s championship for 19 consecutive years, setting a record for men and women by capturing six singles titles, winning a staggering 101 matches on three different surfaces, not once falling short of the quarterfinals in that span.

Evert, of course, established herself as one of the greatest female tennis players of all time; in my humble estimation, she must be regarded as the third best woman player in history behind only Steffi Graf and Martina Navratilova. She collected 18 singles majors altogether, including seven French Open crowns. She was a semifinalist or better in 52 of the 56 Grand Slam events she appeared in. For 13 consecutive seasons—from 1974-86—she won at least one major a year, and that record will surely never be surpassed. She has the best match winning percentage (90%) of any player (male or female) in the modern era. But while her success was far reaching, unfailingly consistent, and multi-faceted, the fact remains: her career essentially began and ended in New York at the U.S. Open, where she played her last major in 1989.

Nowadays, Evert is far removed from those salad days as a competitor. She has been an exemplary mother of three sons (ages 21, 19 and 17), as well as the founder of the Evert Tennis Academy in Boca Raton, Florida. From 1990-2002, she moved into the broadcast booth as a leading analyst for NBC at the French Open and Wimbledon. In 2011, she returned to commentary at Wimbledon for ESPN, and ever since she has been at all of the majors for that network. This will be her third U.S. Open in a row working behind the microphone, and Evert is enjoying that role enormously.

What made her want to resume broadcasting? She explains, “I was at the point where I had one boy in college, one going into college and another in high school, so my life had opened up and the timing was right. If ESPN had asked me five years earlier, it would not have happened. Having been a coach/mentor/owner of the tennis academy for 15 years, I felt I was on the inside of how the game was changing. So when I started with ESPN a few years ago, it was not like I had really been away for nine years. I felt like I had learned much more about the contemporary game, the different spins, the different strategies and different techniques. I was right in the middle of the pulses and development of tennis. If anything, I had more to offer this time than I did in the NBC days. With what they offered, ESPN has been the perfect venue. It is not a full time job but I get to work at the tournaments that every commentator would want to do.”

When Evert stepped into the booth so soon after she retired, she remained close to some of the players, including her old friend and rival Martina Navratilova. That made it an arduous task to speak as freely as she would have liked. Those days are long gone. As she says, “I can look at things logically and in a more realistic way now. I am not afraid to go out on a limb. If somebody is not playing well, I say it. If somebody is not moving well, I say it. When I started broadcasting right after I stopped playing, I was cautious about criticizing Martina or a friend. Now I can look at things more objectively. But it’s funny, because you really can’t win no matter what you do. I get these tweets from people who say, ‘Oh, you are favoring Maria,’ or ‘You favor Serena.’ If Serena is dominating a match, it is not that you are pulling for her, but you are talking about what a great champion she is, how much talent she has, how athletic she is. I just try to say it how I see it.” Are there any special challenges about doing her commentary at the U.S. Open, amidst so much exhilaration and intermittent chaos? She answers, “You have got to bring your ‘A’ game at the U.S. Open, which is more of a show than the other Grand Slams, whereas Wimbledon has its prestige and history and is not as much of a show or as electric as the U.S. Open. There is more reverence to it. But at the U.S. Open, you have got the fans, you have New York City, you have got the lights, you have got the music, you have got all of that excitement. I don’t mean that to bring the other Grand Slams tournaments down because they are all great. But the U.S. Open is more of a show than the other Grand Slams. The other Grand Slams put on a sporting event; the U.S. Open puts on a show.”

I asked Evert if commenting on the matches at the Open can be distracting. She replied, “You can’t get caught up in the hoopla because my job is basically to analyze the match and talk about the players. That is my primary job, to tell the viewers what is happening on the court, what is going on inside the player’s heads, where the momentum changes are happening. I don’t want to lose sight of that because that is really the main reason why I am in the booth: to analyze, to predict, to educate, to inform the viewers. There is so much outer-layering at the U.S. Open. Still, the U.S. Open has a lot of history and it was the first to offer equal prize money for the women in 1973. With the exception of the roof—which they have now announced will happen in a few years—the U.S. Open has always been very much a pioneer in tennis. They even were the first of the Grand Slams to use the tiebreaker. I always enjoy doing commentary there.”

She also found immeasurable contentment from her journey through the seventies and across the eighties as a competitor of the highest order, and a player the fans always wanted to watch. Her 1971 run to the penultimate round was the stuff of dreams. She had won the National 18 Championships earlier in the summer but was already testing the waters of international women’s competition. The year before, as a 15-year-old, she upended none other than Margaret Court in a pair of tie-breaks at a small women’s event in Charlotte, North Carolina, producing an upset that would cause ripples all around the tennis world. In the winter of 1971, she toppled Billie Jean King for the first time on clay in St. Petersburg (King retired at one set all), and won that tournament with additional wins over Francoise Durr and Julie Heldman.

Over the summer leading up to Forest Hills, she led the U.S. to a Wightman Cup victory over Great Britain (defeating Virginia Wade), and took the Eastern Grass Court Championships in South Orange, New Jersey. So she was flourishing in two different worlds, competing against her peers in the juniors, and gaining experience playing against the pros. And yet, while there was a lot of speculation about Evert’s initial appearance at the Open, no one was quite prepared for her sterling run on the grass in New York. Asked how her Open campaign compared to the astounding upset she had over Court the previous year, Evert says, “That win over Margaret Court in Charlotte was nothing compared to the U.S. Open in 1971 and the drama of that year, when I played every match on the center court. I beat Edda Buding and then played Mary Ann Eisel in the round of 32 and went on to beat Lesley Hunt and Francoise Durr in three set matches before I lost to Billie Jean in the semis. The defining match was against Eisel when I saved six match points and the ball looked like a basketball to me. Poor Mary Ann had to live with that for the rest of her life. But the Billie Jean match was also a defining moment for me. The whole thing was like a fairytale for me.”

Evert recollects staying with her aunt and uncle in Larchmont, New York, and remembers, “My Mom [Colette] and I tried to get into [the Westside Tennis Club at] Forest Hills the first day and they wouldn’t let us in at first because I didn’t have my credentials. We had to talk our way in. I was just a little junior player and they kept putting me on the center court in the stadium. Some of the top men [Rod Laver and 1970 champion Ken Rosewall most prominently] did not play the U.S. Open that year so they were looking for somebody to kind of carry the torch. The women weren’t very friendly to me in the locker room because I was kind of a threat to them. Rosie Casals, who later became a doubles partner and a good friend, didn’t talk to me at all. She didn’t like the fact that they had done all the work to start a women’s pro tour and then I came along and was getting all the attention. I felt very isolated and lonely in the locker room but nothing seemed to phase me in those days and I just took everything in stride. That was when my image started to form as far as being unflappable and composed, even at 16. I was just a school girl from St. Thomas Aquinas in Fort Lauderdale and when I got home the whole school and the band came out to the airport. I was more nervous about that than for my matches at the Open.”

Evert reached four consecutive Open semifinals on the grass, but when the event moved to clay at Forest Hills in 1975, she was the overwhelming favorite and was in the midst of an historic 125 match winning streak on that surface. In the final, she came from behind to beat the ever dangerous Evonne Goolagong 5-7, 6-4, 6-2 to secure her first crown at her country’s Championships. “I remember looking up when I won it and my mother was sobbing hysterically and I felt kind of embarrassed because I was more like my Dad in not showing my emotions. Evonne and I had a seesaw match. I knew I should and could beat her on clay because I was more consistent and I had better focus than her, but she was brilliant and so talented. I had to be in the moment with her all the time. Winning that tournament meant a lot to me. You feel the energy of the crowds and know they are pulling for you. That makes you want to go up another level in awareness and concentration.”

After winning the next three U.S. Opens—including the first on the hard courts at Flushing Meadows—Evert was outmaneuvered in the 1979 final by 16-year-old Californian Tracy Austin, a virtual mirror image of herself. Austin played an eerily similar brand of backcourt tennis, striking the ball with unerring reliability, driving the two-handed backhand with sheer conviction, weighing the percentages meticulously. Austin extended her winning streak over Evert to five wins in a row over the coming months, but they collided again in a landmark contest for Evert in the semifinals of the 1980 U.S. Open. Chrissie played one of the finest big matches of her career to defeat Austin 4-6, 6-1, 6-1 after trailing 0-4 in the opening set, and then came from behind again to beat the flowing, flamboyant yet often competitively unhinged Hana Mandlikova 5-7, 6-1, 6-1 in the final to win her fifth U.S. Open.

Asked how she had managed to turn the tables on Austin in a match that reignited her career in many ways, Evert responds unhesitatingly, “The reason I won was Don Candy. The day before I was sitting down in the player lounge and was sitting next to Don, who was Pam Shriver’s coach. He asked me how I felt about playing Tracy, and I told him I didn’t know what to do. Don said, ‘You know, Chrissie, if you let her dictate, she is going to win. One thing you haven’t done the last five times you faced her is to play out of your box. You have got to dictate from the first shot, use your drop shot, and bring her in. You have to control the match.’ I was a counter-puncher so that meant I had to play a game that I normally don’t play. I lost the first set but it was only a difference of one or two points deciding that set. I felt I was playing well and Don’s strategy was working. I came back to win those last two sets 6-1, 6-1 and I was dropshotting, coming in and going for the lines rather than hitting down the middle. I took chances and it worked. Don Candy put a light on in my head.”

When the match was over, Evert headed straight for the telephone with her mother. She called her father, Jimmy Evert, in Fort Lauderdale. Jimmy Evert was her original coach and mentor, and an outstanding teaching professional. But he preferred staying at home rather than enduring the inevitable and almost unbearable tension of watching his daughter in person at the majors. Chrissie started to tell her father that she needed him at courtside for the final, but got all choked up, handing the telephone to her mother, who conveyed Chrissie’s wishes that he be there the next day for the final. Jimmy Evert travelled to see his renowned daughter win a major for the first time from a seat in the arena rather than pacing around his living room.

Chrissie Evert recalls, “I had spoken with my father later on the night before I played Tracy, and told him I wanted to win that match for him. It was great that he came up for the final against Hana. That was a big U.S. Open for me.” She would win the U.S. Open one more time (in 1982), and her Dad was present for that title run as well. But her Open career concluded in 1989, when she visited the two extremes of her game day to day, never knowing precisely what to expect from herself. First, Evert turned the clock back several years when she picked apart Monica Seles ruthlessly 6-0, 6-2 in a vintage round of 16 performance, but then she lost in a straight set quarterfinal to Zina Garrison after leading 5-2 in the first set. That sequence of events—a stirring display of craftsmanship, followed by a sluggish and listless match in defeat—was precisely why she was ready to leave the game at 34; no longer could she automatically summon the consistency and quiet intensity that had once been her trademark. Now the bad days collided too often with the good.

As Evert says, “I was at that point in 1989 still in the top four in the world. But my decision to retire was based on the fact that I was just not consistently waking up every morning all fired up to play. That motivation was starting to wane. I would play better than ever one day but then the next day I wouldn’t want to be out there on the court. I started losing matches because of my lack of motivation. Against Monica I went into my aggressive mode. I dictated play. I had her on the run and played one of the best matches in my career. Two days later I went out against Zina and I had the lead in the first set but I felt flat and not motivated and lost the match. I was glad it happened that way because it proved to me that I had made the right decision to retire. I actually wasn’t devastated by the loss to Zina, who was one of the nicest girls on the tour. I had been competing since I was 8 years old. That is a long time. I had put more mental energy into my matches than most players. I couldn’t afford to let up for one minute. I had to work and grind on every point in my career.”

While the U.S. Open in 1989 was the last tournament she would ever play, Evert did make one last appearance in the Fed Cup for the United States at Tokyo in early October. She had a terrific week, joining forces with Navratilova to lead the Americans to victory, crushing future Wimbledon champion Jana Novotna of Czechoslovakia in the semifinals and Conchita Martinez of Spain in the final. The 6-3, 6-2 victory over Martinez—who would win Wimbledon five years later—was the farewell match of her career. “Not many people knew,” says Evert, “that I played Fed Cup after the U.S. Open that year. In my wins over Novotna and Martinez, I played two of the best matches of my career. I just killed them. So the tennis was still there. Even for two or three years after that, when Martina and I played exhibitions, I played great. But competing day in and day out was not in the cards for me anymore.”

She had competed for nearly two full decades against a cavalcade of great players, across several generations, always keeping her game at a remarkably high level. Evert had played four U.S. Opens on the grass, three more on the clay (winning all of those), and 12 on hard courts. She received a sustained and heartfelt standing ovation after her loss to Garrison that was among the most poignant U.S. Open moments ever; the applause lingered for a long while with some fans moved to tears as they witnessed the departure of an American icon. How does she view the long lifespan she celebrated in New York as perhaps the most popular male or female player of her era?

“So much happened over those years,” she reflects. “I played against a lot of great champions from Billie Jean King and Margaret Court in the beginning of my career to Tracy Austin, Hana Mandlikova and Evonne Goolagong in the middle. My rivalry with Martina Navratilova lasted a very long time (1973-88). Then there was the Steffi Graf and Monica Seles era. It was like going through four different eras of tennis and we played the Open on three different surfaces during my career. No other Grand Slam had that. I saw tennis change and become more of a power game and more athletic over the years. I saw the equipment changes and was around for the move from Forest Hills to Flushing Meadows. The U.S. Open went through a lot of changes and I experienced it all.”

Following up on her point about the emergence of power over the years as the central component in the women’s game, I wondered if Evert felt that the explosive nature of the modern game could be in excess these days with too many matches among the women turning into slugfests, with strategy and tactics often going by the wayside. She replied, “In the last ten years it has really been all about power from the baseline, but I think now we are getting into a new era. I have noticed the players coming to the net more and more, especially against Serena. They know they can’t beat her from the baseline. I sense that it is now becoming more of an all court game with more variety, more drop shots and topspin lobs and volleys. That is because of Serena. She moves better than everyone and has more power than the other players, so they have to come up with something else to beat her. That is going to change the game.”

Williams lost the final of Cincinnati to Azarenka, suffering only her fourth loss of 2013. But it was her second defeat at the hands of Azarenka this season. Does Evert believe that will shake things up in a healthy way coming into the Open?” Yes, I do. I see the other players lifting their level of play, including Li Na, who had her chances against Serena in Cincinnati as well. Sharapova played a good match against Serena in the French Open final. It is not that Serena is losing anything in her game, but the other players because of Serena’s brilliance and dominance are thinking more about strategy against her and they are playing better. It is going to be an interesting Open. Serena is still the favorite but I think we are going to see some three set matches. It will be a very good tournament.”

Evert, of course, will follow it all from close proximity in the ESPN broadcast booth. In the last few years, she has come fully into her own as a commentator, offering penetrating insights, speaking with clarity, candor and conviction, expressing herself with total self-assurance and comfort. She has emerged unequivocally as one of the leading announcers because she approaches her commentary with the same professionalism and tireless work ethic that characterized her time as a player. Above all else, her presentation is stylish, understated and devoid of hyperbole; she is never condescending to her listeners and viewers, and always speaks with a pleasant voice of reason and authority.

Evert concludes, “At ESPN we now broadcast all of Wimbledon and we do the entire Australian Open. In 2015 we will have all of the U.S. Open. I am proud to be with an organization that the Grand Slams believe in so much. In 2015 the only Grand Slam we won’t have from start to finish is the French Open. What makes it all so much fun for me is the team we have at ESPN. To be working every day with Pam Shriver and Mary Joe Fernandez—who are good friends—and then to have Brad Gilbert, Darren Cahill, Patrick McEnroe, Cliff Drysdale and Chris Fowler there—is great for me. There is just no competition among us and no stress. Everybody is supporting one another. It is a team effort. That is what makes this so enjoyable. Doing commentary should be fun, and for me it really is.”